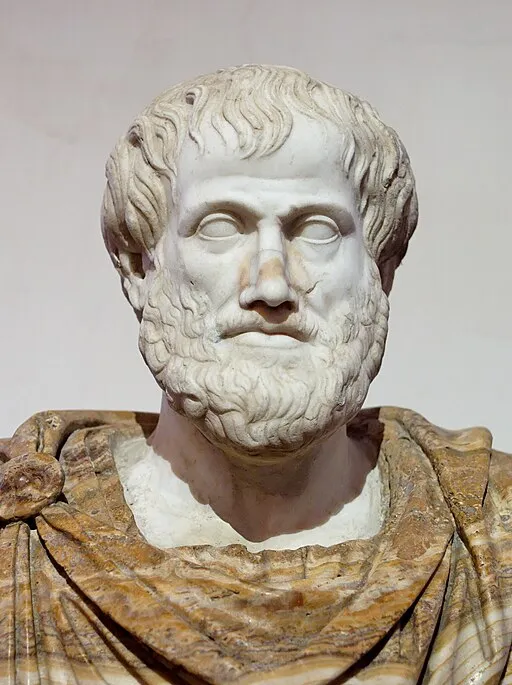

Does Aristotle successfully show that the body requires the soul, and the soul requires the body?

Word Count: 1863

Author: Simon Williams

Topic: Philosophy

Created On: 09 Dec 2023

Last Updated: 28 May 2024 21:08:12

In order to determine whether Aristotle proves that ‘Dsb & Dbs’ (where Dxy is the function ‘x depends on y,’ and ‘s’ and ‘b’ are the arguments soul and body), one must firstly determine how Aristotle defines 'soul' and 'body'. Conventionally, ‘soul’ and ‘body’ are analysed using the Cartesian picture, wherein they are different ‘substances,’ the former immaterial and the latter material. In most traditions, especially religious ones, the soul is the immaterial aspect of the person, and hence exists after bodily death. Aristotle, however, denies the separate existence of the soul from the body, and instead sees soul as the ‘first actuality’ of an organism, an idea which will be elucidated later. This, however, is not the only way that Aristotle defines soul; indeed, the multiple conceptions that Aristotle has for soul means that an answer to the title’s question will have to vary from the affirmative to negative depending on which definition of soul is taken. Under any one of Aristotle formulations of soul, the relation Dsb holds, but it varies as to whether Dbs holds.

In De Anima, Aristotle writes ‘the body is subject or matter’ 1. Central to Aristotelian hylomorphism is the notion that all matter requires form for its existence, since matter is mere potential, and form gives this prime matter an actuality. Hence, Aristotle reasons that matter ‘in itself is not a this.’ 2 Therefore, under this framework, the form is what makes indeterminate matter determinate, and provides the organisation and shape for matter. Since soul is equated with form, the soul must therefore be the shape of the matter that is the body. This explains Aristotle’s remark that ‘It is not necessary to ask whether soul and body are one, just as it is not necessary to ask whether the wax and its shape are one.’ 3 Under such a reading, soul takes a very primitive role, and there’s clearly an inter-dependency of soul and body, wherein, ‘matter is potentiality, form actuality.’ 4 Since soul is form, and body is matter, both require each other; without soul, body would be indeterminate prime matter, without body, there would be nothing for the soul to be a shape of.

However, this basic role of form only makes sense when talking of the form of inanimate objects. The complex role of form for living beings is elucidated by Abraham Edel when he discusses Aristotle’s four causes. He shows how both the final and efficient causes are part of the formal cause. The final is part of the formal since ‘in natural processes the final cause is the mature development of the form itself in the particular materials’5. He similarly talks of Aristotle’s insistence that the ‘the efficient cause is always some activity of the same type that the developed form exhibits.’6 This account of form ‘ceases to be merely shape, organisation, law or formula,’ It’s difficult to see how this complex idea of form can be rectified with Aristotle’s metaphor of the soul as the shape of the wax, and it becomes clearer that body is often rendered independent under this new interpretation.

Aristotle suggests later that ‘the soul is the first grade actuality of a natural body having life potentially within it. The body so described is a body which is organised’7 Aristotle’s description of the body as something which is already organised, renders the meaning of ‘human body’ as that which a modern would take; whilst the soul is simply the life of that body. We may hear an objection at this point: ‘if Aristotle says that the body is matter, and matter is mere indeterminate potential, how can the body be organised?’ The only way around the problem is to see matter as a relative term; this interpretation is endorsed by J.D.G. Evans, who talks about how in a living creature, ‘its matter can be analysed at four levels. In the first place there is the entire physical organism… this is itself the structure of constituent parts, such as face, hands and heart… we reach a third level when we see that these material components are themselves structures composed of material stuffs such as blood and flesh… the blood and flesh can themselves be analysed into more elementary constituents… the four traditional elements, fire air, water and earth.’ 8 Thus, the fully organised body can be seen as the immediate matter of the soul, whilst the prime matter that fundamentally constitutes the body would be the soul’s ultimate matter, ‘in every case, the earlier sum is the matter for the next one on the list.’ 9 This interpretation of matter thus enables us to make sense of the interpretation frequently given by Aristotle of the soul as ‘the form of a natural body having life potentially within it.’ 10 It’s important, firstly, to show what these quotations from Aristotle indicate. They suggest that the soul just is the life of the body, it’s not the efficient cause; it’s the life itself. David Bostock agrees with this estimation when he argues ‘it is not, in our sense, the cause of that, something which brings it about… but is rather the working of the machine itself.’ 11 We can see that you can’t have life without an organised body in the first place, thus soul depends on body. The body itself, however, does not depend on life for its existence, since a corpse is still an organised body. Under this interpretation of soul and body, Aristotle only shows asymmetrical dependency.

Another Aristotelian interpretation of soul is one in which the soul is the function of the body – by this I mean its primary activity, or possibly its primary purpose. Aristotle writes ‘suppose that if the eye were an animal – sight would have been its soul; for sight is the substance or essence of the eye.’12 If sight is to eye as soul is to body, then the soul must be the primary function and purpose of the body - this conception of soul is very similar to final cause. If the soul is the purpose of the human body, we must ask ourselves, ‘what possible purpose can there be beyond living?’ Bostock raises this point when he says ‘what is the stomach for? It is for digesting food… what is that for? It turns the food into a form that is suitable for nourishing the body… what is nourishment for? Without it the body cannot go on living. What is living for? Here we stop.’13 If the function of human beings is living, and if the soul is the function of human beings, then it’s clear that the soul is simply the life of the body. This, however, differs in no way from his previous conception of the soul as ‘the form of a natural body having life potentially within it.’ 14 As was agreed in the previous paragraph, such a reading leaves soul dependent on body, but not vice versa.

If, however, we are to take ‘function’ to be something other than living, then it must be something non-biological (one might suggest that ‘reproduction’ is the ultimate function, but then reproduction is the creation of life), since it is made clear in the previous paragraph that life is, biologically speaking, the final cause – it is not itself for anything. When Aristotle talks about the four types of soul, he maintains that the rational soul is unique to human beings: ‘no animal except man has the power to think, and he has all the kinds of soul here distinguished.’ 15 It would be reasonable to suggest, therefore, that the human function is reason, on the basis that it is (or at least, in Aristotle’s estimation) unique to humanity. This idea has support in the Nichomacean ethics where Aristotle describes the end of human existence to be ‘a practical life of the rational kind.’ 16 Under this analysis, the body would have to be something which is both organised and living, since it is impossible for something which is not living to be able to reason. If one takes soul as function, body must mean living organism and soul must be equivalent to ‘what that life is primarily for’, i.e. reason). Aristotle makes it clear that our mental life always has a material component – in other words, every thing which we think must be an aspect of both the soul and the body. For example, Aristotle shows how anger can be defined as an ‘appetite for returning pain for pain’ or ‘a boiling of the blood or warm substance around the heart.’ 17 Here, we can see that every mental aspect must be represented physically. It may be argued that anger differs from something like reason, however, Aristotle still believes thought to be just as bound up with the body, since thinking ‘too requires a body as a condition of its existence.’ 18 Under this understanding of soul as function, and function as ‘practical reason,’ it’s clear that the soul requires the body, since Aristotle believes all mental processes to have a physical aspect. But, again, it’s not clear that the body requires the soul, since a body needn’t be able to reason in order to exist.

In summary, the question of whether Aristotle proves soul to be dependent on body and vice versa, hinges on which Aristotelian notion of form and body you are analysing. Only in the instance in which body is prime matter and soul is material shape and organisation, does body depend on soul. In all other instances, wherein body is already taken to be an organised whole, the soul only serves to predicate this whole. For example, the soul takes on the roles of predicating a body with life, or with a function – here the matter is the independent substance, whilst the soul is that which predicates the matter.

References

1,4,10,14 Aristotle, De Anima, Book 2, part 1, page 3

2 Aristotle, De Anima, Book 2, part 3, page 3

3 Aristotle, De Anima, Book 1, 412b 6-9

5,6 Abraham Edel, Aristotle and his Philosophy, University of North Carolina Press, 1982, page 62

7 De Anima, Book 2, Part 1, Page 4

8 J. D. G. Evans, Aristotle, St Martin’s Press, 1987, page 64

11 D. Bostock, ‘Aristotle’s Theory of Form’ (In D.Bostock, Space, Time, Matter, and Form: Essays on Aristotle’s Physics), Oxford, 2006, page 95-96

12 Aristotle, De Anima, Book 3, Part 1, page 4

13,15 D. Bostock, ‘Aristotle’s Theory of Form’ (In D.Bostock, Space, Time, Matter, and Form: Essays on Aristotle’s Physics), Oxford, 2006, page

16 Nichomacean Ethics, Book 1, Section 6

17,18 De Anima, Book1, Part 1, Page 2.

User Feedback

-

Alfie: Hi mate